KOZHIKODE- India: When the sun sets and the dust settles, the bustling gullies of Kozhikode city slip into the rumblings of the tabla and harmonium. The melodious humming of Mohammed Rafi, the romantic tunes of Talat Mahmood, or the soulful singing of Mukesh fills the air. One may wonder how the busy thoroughfare transforms into mind-blowing ghazals and qawwalis—and that too every day. This is the unique nightlife of this historic coastal town.

You won’t find dance bars or trendy pubs downtown, but along the beach and in hidden corners, you’ll discover plenty of music paired with simple eateries. This isn’t a new trend or a lifestyle shift; it dates back to the 1950s and even earlier. The legendary musical composer M.S. Baburaj and his contemporary Kozhikode Abdul Khader—better known as the Malabar Saigal—were products of this city. They were very much present in the streets of Kozhikode. Baburaj began his career as a vocalist in Mappilappattu, a musical genre deeply popular among the Muslim community of Malabar. He later joined the Malayalam film industry, contributing evergreen hits that continue to resonate. The musical legacy they created didn’t fade with them; it has lived on through generations.

In Kozhikode, people love football and music more than politics. This shared passion forms a binding thread that nurtures coexistence in this diverse part of Kerala.

The city has a rich tradition of trade and commerce. Traders from Arab countries, Portugal, France, and later the British landed here for mercantile business. The remnants of that past can still be traced in the ramparts and old structures of Kozhikode.

Though native speakers may be less familiar with Hindi and Hindustani music, the most adored singer remains Mohammed Rafi. A memorial stands in his honor, and a street is named after him—such is the depth of affection. The city isn’t averse to other versatile legends like Kishore Kumar, Mukesh, Manna Dey, K.L. Saigal, and Talat Mahmood. Yet it was Rafi in Hindi and Baburaj in Malayalam who truly dominated the streets.

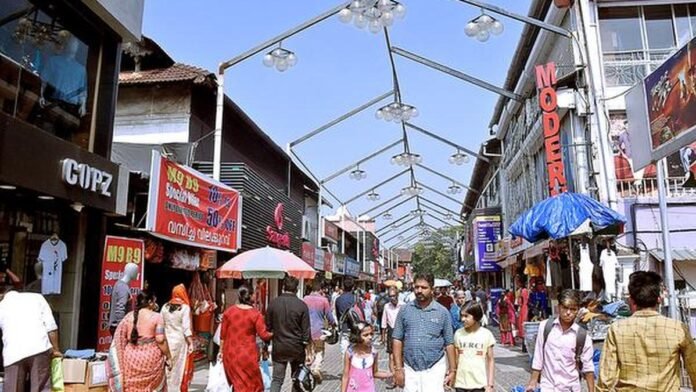

Big Bazar, the largest rice market in Kerala, lies close to SM Street (Mittayi Theruvu), a vibrant UNESCO-recognized heritage site. By day, it’s always bustling with big containers and mini trucks—walking along the road can be a challenge amid the thriving business.

But when darkness falls in the evening, this busy market turns into a darbar of music. The upstairs of old buildings fill with singers and artists. It may sound unusual, but that’s Kozhikode: a market that becomes a musical haven. Porters, auto drivers, and market laborers love music so deeply that they gather in these modest setups to entertain themselves—a much-needed respite after a day of hard work.

These gatherings, locally known as thattinpuram clubs (literally “attic” or makeshift upstairs clubs), feature bare-minimum facilities: a few plastic chairs, a makeshift podium, one harmonium, and a tabla. Some places now include keyboards. Anyone can step up and sing for free—no restrictions on genres, as long as the performer knows the song. The mehfil—an Urdu term for a musical gathering—often lasts late into the evening, and participants return home only to reunite the next night.

This is more than mere entertainment; it’s a gathering of friends and community members that strengthens social cohesion. No one needs to be a professional singer—any amateur can perform. In this way, it serves as an informal training platform for budding artists. Something truly unique to this city, perhaps rare anywhere in the world.

While the traditional thattinpuram clubs continue to echo with timeless melodies, Kozhikode’s musical spirit remains vibrant and evolving. Modern initiatives like the Kerala Ghazal Foundation organize contemporary mehfil events, blending ghazals, qawwalis, and even Malayalam folk fusions, keeping the legacy alive in venues such as Town Hall and cultural festivals. Clubs like Calicut Kalamandir in Valiyangadi still draw laborers and music lovers for soulful evenings, preserving the grassroots charm. Globally, similar open, community-driven musical gatherings can be found in the qawwali mehfils at Sufi shrines like Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi or the passionate Sufi nights in Lahore, Pakistan—though Kozhikode’s version stands out for its everyday, market-integrated accessibility and inclusivity, where working-class enthusiasts turn humble attics into stages without tickets or hierarchies.

While the traditional thattinpuram clubs continue to echo with timeless melodies, Kozhikode’s musical spirit remains vibrant and evolving. Modern initiatives like the Kerala Ghazal Foundation organize contemporary mehfil events, blending ghazals, qawwalis, and even Malayalam folk fusions, keeping the legacy alive in venues such as Town Hall and cultural festivals. Clubs like Calicut Kalamandir in Valiyangadi still draw laborers and music lovers for soulful evenings, preserving the grassroots charm. Globally, similar open, community-driven musical gatherings can be found in the qawwali mehfils at Sufi shrines like Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi or the passionate Sufi nights in Lahore, Pakistan—though Kozhikode’s version stands out for its everyday, market-integrated accessibility and inclusivity, where working-class enthusiasts turn humble attics into stages without tickets or hierarchies.